Botere publikoek diseinatzen eta inplementatzen dituzten politiken edukiek eta prozesuek baldintzatzen dute ingurua. Berebiziko egunerokotasuna du gainera gaiak egungo testuinguru bihurrian. Zer egin dezakete herritarrek? Noraino ulertzen ditugu politikok? Blog honek politiken ulermen eta neurri apalagoan, berauen definizioan lagundu nahi du herritarrengandik gertuenekoa den esparruan: esparru lokalean

2012(e)ko irailaren 17(a), astelehena

Zerbitzu publikoetan klausula sozialak ez dira nahikoa

Etiketak:

klausula sozialak,

kooperatibizazioa,

lan hitzarmenak,

mutualizazioa,

outsourcing,

politikak,

prezioa,

pribatizazioa,

udal zerbitzuak,

zerbitzu lokalak,

zerbitzu publikoak

2012(e)ko irailaren 14(a), ostirala

Zerbitzuen pribatizazioa gaur, oztopoak eta posibilitateak (I)

Administrazio publikoek, eta tartean udalek, zerbitzu publikoak kanporatzeko joera izan dute azken hamarkadotan. Joera hauek titularitate aldaketa ekarri izan dute zenbaitzuetan, baina orokorrean zeharkako gestiora jo izan da, hau da, kontratazio publikoaren bidez enpresa pribatu baten esku jartzera zerbitzua, baina titularitatea oraindik administrazioak gordez. Hainbat arrazoi erabili izan dira argudio modura:

Baina kontua da zerbitzuaren gestioa kanporatzeak ere hainbat arazo sortzen dituela, besteak beste honakoak:

- Arrazoi finantzarioak: defizit publikoak jasangaitzak izatea, eta zerbitzu publikoak finantza ikuspegitik eraginkorragoak egiteko beharra

- Arrazoi ekonomikoak: uste zabaldua da enpresa pribatuek eraginkortasun handiagoa dutela erakunde publikoek baino. Dena dela, uste horren azpian akats bat ere badago, enpresa pribatuek ere administrazioen akats berberak erakusten baitituzte oligopolio edo lehia murriztuko egoeretan

- Legezko arrazoiak: hasiera batean europar nazioarteko esparrutik etorritako araudiek lehia askeari ematen dioten garrantziak zenbait jarduera publiko esparru publikotik ateratzera behar du. Bestalde horri gehitu behar zaio funtzio publikorako lan eskaintzak 2014ra arte izoztuta egotea

- Arrazoi ideologikoak: korronte ideologiko batzuk sektore publikoak jarduera ekonomikoan aritzearen aurka egon izan dira betitik.

- Gestioaren kontrola urrundu egiten da bi arrazoirengatik

- Administrazioak berak beste erakunde baten gaineko kontrola egiteko ahalegina handitu egin behar duelako

- Zerbitzuaren arduraduna den administrazioa eta zerbitzuaren erabiltzailearen artean maila bat gehiago (zerbitzua gestionatzen duena) ezartzen delako

- Zerbitzua ematerakoan administrazioak duen helburua (onura publikoa) eta enpresa pribatu batek duena (oro har, kapital enpresetan mozkinak maximizatzea) ezberdinak direlako, eta ezberdintasun honek erabakiak eta jarduerak asko baldintzatzen dituelako

- Zerbitzu hartzaileekiko jarrera ere ezberdina da, zeharkako gestioaren kasu batzuetan bezero modura hartzera jotzen baita erabiltzailea, eta horrek urruntze bat ere badakar

- Mozkinak maximizatzeko zeharkako gestioan dabiltzan enpresen logikak zerbitzuaren kalitatearengan edo zerbitzu emaile diren langileen baldintzengan eragin negatiboa izan dezake

- Zerbitzu ematetik datorren aktibitate ekonomikoak sortzen duen irabazia kasu askotan (batez ere kontratazio handiko enpresen kasuan) herritik eta lurraldetik kanpora joaten da enpresaren erroak beste nonbait daudelako

Panorama hau marraztu ondoren, gai hau landuko dugun hurrengo udal politikek arazo hauek apaltzeko edo konpontzeko izan ditzaketen aukerak aztertuko ditugu.

Etiketak:

mozkinak,

onura publikoa,

outsourcing,

politikak,

pribatizazioa,

titularitatea,

udal zerbitzuak,

zerbitzu lokalak,

zerbitzu publikoak

2012(e)ko irailaren 7(a), ostirala

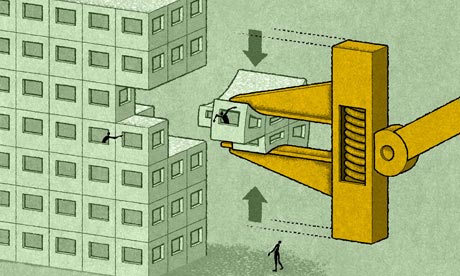

Public sector outsourcing: finally, an unfairness we can do something about

Shareholders and CEOs are benefiting from the outsourcing boom. But done differently, society could look much fairer

Illustration by Matt Kenyon

'Public sector commissioning": I can't think of a phrase that conveys something so important and yet sounds so soporific. The worst thing about it is that, the minute you stop being bored, you will immediately become angry. It's like Britain's Got Talent.

At the weekend the FT reported that outsourcing was booming, with a surge in contracts not seen since the 1980s relating to prisons, police forces, defence and health. We knew this was coming, of course – the first wave of police force privatisation was leaked to the Guardian in March. Last November, the first tender documents went out for nine prisons (Birmingham went to private hands in April).

What was the health and social care bill, if not an invitation to private companies to bid for contracts? The FT says this new tranche of work will be worth £4bn; but even though this is certainly a surge, it is a drop in the ocean of the public sector as a whole which, in 2009-10, spent £236bn on goods and services. It's enough that, if it were spent wisely, on companies with some basic principles regarding, say, the pay differential between the top and the bottom, society would look very different. At the moment, it is not being spent wisely.

Here's what goes wrong: first, we're often dealing with a unique service. The police, for instance, which this paper reports today will soon be run by G4S. What other business of the market could be held equivalent to a police force? When it's never been privatised before, it's hard to lodge an effective opposition, beyond "I just don't like outsourcing".

But just as it's hard for us to launch an opposition, it's hard for local authorities to commission. Who do they know who has experience of taking over a police force? Nobody. What kind of irresponsible idiot would hire someone with no experience? So the way the tender document is designed is that only people who can prove experience of dealing with huge budgets need apply.

Indeed, only big firms could afford the cash it costs to make the opening bid. This leads to so-called monocultural situations in which companies spring up who only deal with government contracts (A4e, for instance has had millions of pounds of public money, and it never struck anyone as strange that nobody else wanted to employ it – although A4e claims it has contracts with the private sector, most of its income comes from government contracts). They become the only viable bidder, whose efficacy is rarely tested, and when it is it doesn't matter because they're – this old chestnut – too big to fail. The possibility of corruption, while it looms large, is actually only ancillary. The central problem is that it encourages companies to expand into areas in which they have no expertise and squeeze out smaller, often charitable enterprises already working in that area.

So, for instance, Prospects started off as a south London careers service. It won a £71m contract to do Ofsted's early-years inspections in 2010 (a reminder that outsourcing didn't start with the coalition). Then it got a work programme contract in the south-east worth £50m. Then it subcontracted its "clients", who became those famously shafted Jubilee stewards.

I use this example deliberately: as a firm with no shadow of a misdeed, just a lot of government money, for work it sometimes subcontracts and doesn't have to take responsibility for. Its executive chairman, Ray Auvray, makes £193,354 a year – this actually isn't very much, by the standards of his peers.

The One Society showed last year that private companies whose main income came from the public sector paid their chief executives far more than the highest paid public sector employee. "Serco, which receives over 90% of its business from the public sector, paid Christopher Hyman an estimated £3,149,950 in 2010. This is six times more than the highest paid UK public servant and 11 times more than the highest paid UK local authority CEO."

But if Prospects doesn't overpay its executive chairman, it does turn a substantial yearly profit of £12.6m. It does not seem unreasonable to ask whether rewarding shareholders is an inevitable cost in this sector. Why can't this work be undertaken by not-for-profit organisations, many of which were established for the very purpose of doing it?

The answer is because charities are never large enough to tender for contracts. Instead they are used as "bid candy" for large corporations to demonstrate a sense of social responsibility. The charities often secede from the deal later on, either because they don't get any referrals or because they're only given the "hard-to-reach" cases (15 charities pulled out of the work programme in the second half of last year for these reasons).

This is replicated in every sector: who can afford to bid for a prison? Capita,G4S, Serco, Sedexo; possibly a foreign company of a similar size, GEOAmey. We can't see who's in the running due to commercial confidentiality; all we can do is await the result and remark upon how inevitable it was. The lowest bidder will win, and its "efficiency saving" will generally be that it has managed to drive down wages. Especially in the adult social care sector, how could it possibly be otherwise? Their product is care; the only thing that can become cheaper is the carer or the cared-for. Then we sit back and marvel that 3.6m households are "one push from penury", not because of unemployment, but because wages are too low.

The point is not that it's unfair – it's that here, finally, is an unfairness that we can do something about. We just have to wake up.

Twitter: @zoesqwilliams

- © 2012 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

Oraingo honetan gaur egun hainbat buruhauste ematen dituen beste gai garrantzitsu bati buruz arituko gara: JUBILAZIOA.

Azken urteetan krisia dela eta, jubilazio adina luzatu egin da lurralde askotan. Langile hauek lanean jarraitzea erabakitzen dute 65 urterekin jubilatuz gero kobratuko duten pentsio miseriak ez dielako bizi kalitate onik bermatuko.

The Guardian prentsa Ingelesean honi buruz idatzi dute honako artikulu honetan.

Can you ever afford to retire?

Can you ever afford to retire?

With

new statistics showing that 1.4m people of pension age are still

working, we look at what people should do to be able to retire

Public sector workers such as Anna-Marie

Jones still enjoy the most generous benefits of any type of pension

scheme. Photograph: Mark King

Will you ever be able to retire? The number of people working

past state pension age has nearly doubled in the past 18 years,

according to figures released by the Office for National Statistics.

The figures show that 1.4m people above the state pension age were still employed in 2011, compared with 753,000 in 1993.

Some work for social interaction, job satisfaction and to provide structure to their lives. But Ros Altmann, director general of Saga, says many are forced to work for an altogether more worrying reason: they simply don't have enough to live on if they retire. This, she says, "may be especially true for women who may have returned back to work from taking time off and have very little pension provision".

Darren Philip, policy director at the National Association of Pension Funds agrees: "Having more older people in the workforce will become the norm. Many are choosing to ease into their retirement for social and financial reasons, and part-time work is a popular option.

"The problem comes when people want to retire but end up stuck at work because they cannot afford to leave. With half the workforce not saving into a pension, this is going to become a painful reality for millions."

The average 50-year-old intends to retire at the age of 61.5 years, having paid off their mortgage at 58.5, according to the insurer MetLife. This is highly unlikely to happen, though: MetLife points out that the same average 50-year-old has £54,300 saved in their pension funds, less than half the £122,800 they would need to generate about £7,000 a year in annuity income. That, in addition to the basic state pension, should just about add up to an annual income of £14,400 – the poverty line as defined by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Ian Naismith, head of pensions for the insurer, says: "We've seen a significant increase this year in public sector workers [who are most likely to have the option of joining a final salary scheme] who say they're not currently contributing to any pension – up from 14% to 19%. However, we think an equally significant factor may be loss of confidence. Only 37% are confident that their scheme will pay out as planned, and only 42% believe their main income will come from a defined benefit pension, down from 51% last year."

It is difficult to think about putting money towards retirement when prices are rising and salaries are not. But it is vital if you want the option of retiring with a decent standard of living. So how should people in different sectors of the work market approach this problem?

Naismith says: "For someone running their own business, the priority is to make it successful and that may take up all their financial resources. They may also feel that they can help fund their retirement by selling their business at some stage, but they should bear in mind that their business may not raise the amount they expected, or could even fail. The government is planning to raise state pensions for self-employed people, but only to about £7,300 a year."

Cyrus Tchahardehi, 37, launched an online hospitality training and networking business, Rehoba, in 2011 after leaving his job as a wine supplier. He says: "While I love having my own business, saving for retirement was easier when I had a company pension plan. I managed to save around £45,000, all of which has gone into the business.

"I will reassess my situation once all of my borrowings are reimbursed. I don't really know at what age I would wish to retire, but ideally I see myself retiring in my early to mid-fifties and dabbling in a few businesses."

Martin Bamford, a chartered financial planner with independent financial adviser Informed Choice says: "Cyrus should focus for a few years on achieving profitability within the business and then work with his professional advisers to understand the most tax-efficient ways in which to extract these profits by making pension contributions. Cyrus appears to display the typical entrepreneurial mindset when it comes to taking risks with his money, so he might want to take less risk within his pension funds to balance things out."

Robert Jessel, a 31-year-old copywriter who lives in south-west London with his wife, an academic, admits he will "probably never be able to stop working entirely". The couple do not own their own home, and Jessel says that while he had an occupational pension for three months in his last job, it will probably take the introduction of auto-enrolment – the automatic opting in of staff into their employer's pension scheme – before he starts saving again.

"The current economic climate is a big shock to people my age. I grew up and had my first job in boom years. Now we're just trying to get by. I won't really be able to save anything until I'm earning £40,000, but my wife has completed her PhD and is looking for a job. That should help."

Bamford says: "Robert is not alone in waiting to be forced to save for his retirement. But the introduction of auto-enrollment is unlikely to encourage him to save at the level he needs to have a financially secure retirement. A plan based on continuing to work forever is rarely practical or realistic. Sickness or lack of work are both factors that tend to force people into retirement much earlier than planned.

"At 31 years old, Robert is young enough to make a real difference to his retirement if he is prepared to save. But if buying a first home is his priority, he still has a few years before he really needs to start worrying about tying money up in a pension. In the meantime he should save what he can in flexible and accessible cash savings accounts and Isas."

Many are worried they will end up with less retirement income following the government-instigated changes to public sector final salary schemes, but according to the research more than half say they are unable to save to improve their retirement income.

Anna-Marie Jones, a performance analyst at Brighton and Hove City Council, contributes £172 a month towards her public sector final salary scheme. She says: "I will always work and want to work in the public sector. But I can't afford to contribute to another pension scheme, and although I do have regular savings, I want to be able to access them at any time if there is an emergency."

Jones is doing the right thing, Bamford says: "You would expect Anna-Marie to be in the most financially secure position in retirement. Despite the latest series of reforms, public sector pensions typically offer the most generous benefits of any type of pension scheme.

"Anna-Marie will receive a projected benefit statement once a year which she should review carefully. And as she gets closer to her retirement age, it will become easier to understand how this pension income will support her desired lifestyle in older age. Making regular savings to create a cash fund alongside her pension benefits is a smart move. Once she has built up an emergency fund equivalent to three or six months' typical expenditure, Anna-Marie might consider creating a longer-term savings fund or even investing in an Isa."

Women with young children are able to claim child benefit, but

in families where at least one partner earns over £50,000 a year this is

due to be clawed back through the tax system from 7 January next year.The figures show that 1.4m people above the state pension age were still employed in 2011, compared with 753,000 in 1993.

Some work for social interaction, job satisfaction and to provide structure to their lives. But Ros Altmann, director general of Saga, says many are forced to work for an altogether more worrying reason: they simply don't have enough to live on if they retire. This, she says, "may be especially true for women who may have returned back to work from taking time off and have very little pension provision".

Darren Philip, policy director at the National Association of Pension Funds agrees: "Having more older people in the workforce will become the norm. Many are choosing to ease into their retirement for social and financial reasons, and part-time work is a popular option.

"The problem comes when people want to retire but end up stuck at work because they cannot afford to leave. With half the workforce not saving into a pension, this is going to become a painful reality for millions."

The average 50-year-old intends to retire at the age of 61.5 years, having paid off their mortgage at 58.5, according to the insurer MetLife. This is highly unlikely to happen, though: MetLife points out that the same average 50-year-old has £54,300 saved in their pension funds, less than half the £122,800 they would need to generate about £7,000 a year in annuity income. That, in addition to the basic state pension, should just about add up to an annual income of £14,400 – the poverty line as defined by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Even if you are saving

hard, the crisis in Greece and Spain is making matters worse. Unless you

belong to a final salary or defined benefit pension scheme, your

savings will have been hit by the stock market turmoil.

Incredibly, some of those entitled to join a defined benefit scheme – regarded as the crème de la crème of pensions

– are not taking advantage of the opportunity. Others believe their

scheme will not provide enough income, according to research by Scottish

Widows.Ian Naismith, head of pensions for the insurer, says: "We've seen a significant increase this year in public sector workers [who are most likely to have the option of joining a final salary scheme] who say they're not currently contributing to any pension – up from 14% to 19%. However, we think an equally significant factor may be loss of confidence. Only 37% are confident that their scheme will pay out as planned, and only 42% believe their main income will come from a defined benefit pension, down from 51% last year."

It is difficult to think about putting money towards retirement when prices are rising and salaries are not. But it is vital if you want the option of retiring with a decent standard of living. So how should people in different sectors of the work market approach this problem?

Self-employed

People running their own businesses are the least likely to be saving towards their retirement, with just 36% putting anything into a pension. One fifth of those questioned for the Scottish Widows survey believed the bulk of their pension would come from a defined benefit scheme, indicating they expect to survive on contributions to pension schemes run by previous employers.Naismith says: "For someone running their own business, the priority is to make it successful and that may take up all their financial resources. They may also feel that they can help fund their retirement by selling their business at some stage, but they should bear in mind that their business may not raise the amount they expected, or could even fail. The government is planning to raise state pensions for self-employed people, but only to about £7,300 a year."

Cyrus Tchahardehi, 37, launched an online hospitality training and networking business, Rehoba, in 2011 after leaving his job as a wine supplier. He says: "While I love having my own business, saving for retirement was easier when I had a company pension plan. I managed to save around £45,000, all of which has gone into the business.

"I will reassess my situation once all of my borrowings are reimbursed. I don't really know at what age I would wish to retire, but ideally I see myself retiring in my early to mid-fifties and dabbling in a few businesses."

Martin Bamford, a chartered financial planner with independent financial adviser Informed Choice says: "Cyrus should focus for a few years on achieving profitability within the business and then work with his professional advisers to understand the most tax-efficient ways in which to extract these profits by making pension contributions. Cyrus appears to display the typical entrepreneurial mindset when it comes to taking risks with his money, so he might want to take less risk within his pension funds to balance things out."

Private sector employee

The average income someone in the private sector expects to retire on is £24,370, according to the 2012 Scottish Widows pensions report. While this is slightly below the UK average, it is nearly double the £13,000 that the average saver retiring at age 65 is actually set to receive. One in 10 would like to retire at 55, but 24% think they will only be able to retire when they are 70 or over.Robert Jessel, a 31-year-old copywriter who lives in south-west London with his wife, an academic, admits he will "probably never be able to stop working entirely". The couple do not own their own home, and Jessel says that while he had an occupational pension for three months in his last job, it will probably take the introduction of auto-enrolment – the automatic opting in of staff into their employer's pension scheme – before he starts saving again.

"The current economic climate is a big shock to people my age. I grew up and had my first job in boom years. Now we're just trying to get by. I won't really be able to save anything until I'm earning £40,000, but my wife has completed her PhD and is looking for a job. That should help."

Bamford says: "Robert is not alone in waiting to be forced to save for his retirement. But the introduction of auto-enrollment is unlikely to encourage him to save at the level he needs to have a financially secure retirement. A plan based on continuing to work forever is rarely practical or realistic. Sickness or lack of work are both factors that tend to force people into retirement much earlier than planned.

"At 31 years old, Robert is young enough to make a real difference to his retirement if he is prepared to save. But if buying a first home is his priority, he still has a few years before he really needs to start worrying about tying money up in a pension. In the meantime he should save what he can in flexible and accessible cash savings accounts and Isas."

Public sector employee

Nearly half of public sector workers would like to retire at the age of 60 or younger – well below the government's planned retirement age for public sector schemes. Yet 37% of those questioned for the Scottish Widows survey are putting aside nothing in addition to their occupation pension to enable this to happen.Many are worried they will end up with less retirement income following the government-instigated changes to public sector final salary schemes, but according to the research more than half say they are unable to save to improve their retirement income.

Anna-Marie Jones, a performance analyst at Brighton and Hove City Council, contributes £172 a month towards her public sector final salary scheme. She says: "I will always work and want to work in the public sector. But I can't afford to contribute to another pension scheme, and although I do have regular savings, I want to be able to access them at any time if there is an emergency."

Jones is doing the right thing, Bamford says: "You would expect Anna-Marie to be in the most financially secure position in retirement. Despite the latest series of reforms, public sector pensions typically offer the most generous benefits of any type of pension scheme.

"Anna-Marie will receive a projected benefit statement once a year which she should review carefully. And as she gets closer to her retirement age, it will become easier to understand how this pension income will support her desired lifestyle in older age. Making regular savings to create a cash fund alongside her pension benefits is a smart move. Once she has built up an emergency fund equivalent to three or six months' typical expenditure, Anna-Marie might consider creating a longer-term savings fund or even investing in an Isa."

Rather than claim child benefit only for the higher-earning partner to have to fill in a tax return and pay it back in extra income tax, some women might choose not to claim in the first place. But George Bull of accountant Baker Tilly says this would be a mistake, as it could result in the woman losing out on state pension.

He says: "If a woman simply does not claim [child benefit], she gets nothing: nothing in cash and nothing on her NI record. However, under the new rules, she will be able to claim but elect not to be paid, which is subtly different: she will not collect the child benefit, so there will be no tax clawback, but she should still be credited with the minimum NI record needed to qualify for state pension."

- © 2012 Guardian News and Media Limited or its affiliated companies. All rights reserved.

Harpidetu honetara:

Mezuak (Atom)